The Pine Ridge Reservation

The Pine Ridge Reservation

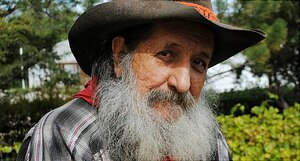

Joseph Whiting, of Kyle, SD, stands near his home on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. The reservation encompasses Oglala Lakota County. Whiting strokes the coarse hairs of a gray beard and waves his hand over an imaginary map. It’s a tour of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation: from his home in Kyle, South Dakota, to the rock outcroppings at the border of the Badlands, past sun-drenched sunflower fields and golden mullein stalks to the 1890 site of the Wounded Knee Massacre.

He’s 75, a wooden cane propped at his side — a crutch for the swollen knee that bears the scars of knee replacement surgery. For all the pride he has in his homeland, there is an equal amount of pain. Pain that people die young. Pain that he is among thousands of Lakota diagnosed with diabetes. Pain that he can tell you exactly where to get crystal meth.

“I could tell you 10 places within a mile of here,” he says.

It’s just one piece of a complex puzzle that has marked Oglala Lakota County with the lowest life expectancy rate in the country. There is a way to change that, says. Donald Warne, MD, but it will take years and a seismic shift in the social and political climate of those on and off the reservation.

“It’s heartbreaking and enraging,” says Warne, associate dean for diversity, equity, and inclusion in the School of Medicine and Health Sciences at the University of North Dakota. “It doesn’t have to be this way.”

Native American populations like those in Oglala Lakota County have the highest rates of health disparities in the nation, including higher infant mortality rates, suicide, diabetes, heart disease, and alcohol-related accidents. Oglala Lakota County also covers more than 2,000 square miles and is inside the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, which is nearly 3,500 square miles in southwestern South Dakota — the second-largest reservation in the United States. The Oglala Lakota, or Oglala Sioux, are one of seven subtribes of the Lakota who make up the Great Sioux Nation. The land is a mix of alternating swaths of dry prairieland, rolling pine-covered ridges, hills, the Badlands, an area of rugged terrain and extreme temperatures. The county’s population is difficult to confirm. The U.S. Census Bureau reported 14,354 people in 2017, however, some estimates put it closer to 30,000.

Warne, who was born on the reservation, said the health statistics of his people are alarming but not impossible to conquer. The problems are deeply rooted in historical trauma, racism, and child maltreatment. “Then you have on top of that poverty, also limited opportunities for healthy food, marginalization, and social discrimination,” he says. It’s the perfect combination of obstacles.

“It will take more than one solution,” he says. “What we need is an investment in changing the social circumstances, and it will take an entire generation to resolve.”

Jeff Henderson, president and founder of the Black Hills Center for American Indian Health, has spent years studying the health of the reservation, working to provide useful data and research that leaders can use to improve its health.

“Tribal people once controlled 100% of the land mass in the U.S., and it was whittled down to 2.5%,” he says. “We had tremendous natural resources taken from us. There are political, economical, and social policies that limit the life potential of people. What does decade after decade of profound inter-generational poverty and joblessness do to a community? It’s heavy substance abuse, violence, and hopelessness.”

Cancer: The effects are far-reaching.

A Lakota man on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation has a life expectancy 15 years shorter than a non-Native man living just 100 miles away in Rapid City, SD. The life expectancy on the reservation is 62 years for men and 71 for women.

Ground zero for poverty in America is right here.

Jeff Henderson, Black Hills Center for American Indian Health

According to a study by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), each year, people will die in the county at twice the rate of the rest of the country. Oglala Lakota County had a death rate of 1,618 per 100,000 people in 2014. The rate for the United States the same year was 785 per 100,000. The most serious health concerns include diabetes, cancer, heart disease, and stroke. Almost a fifth of the population has been diagnosed with diabetes, and more than 40% smoke. Obesity affects nearly half of all adults.

Experts say poverty plays a major role in the health status of Oglala Lakota County residents. The median household income was $26,330 from 2012 to 2016, with almost half of its residents below the federal poverty line.

“Ground zero for poverty in America is right here,” Henderson says. “The inter-generational poverty is profound. [This county] has never left the list of the 10 poorest counties.”

Half the people reported living in homes with at least one of four problems: overcrowding, high housing costs, or lack of kitchen or plumbing facilities.

“There is tremendous overcrowding and a lack of housing,” Henderson says. “there is absolutely a relationship between overcrowding and infectious illness, mental health, violence, substance abuse, and adverse childhood experiences.”

Alcohol

If Henderson could call out one health issue that continues to plague Oglala Lakota County, it’s alcohol abuse.

Henderson founded the Black Hills center in 1998 after working as a doctor for the Indian Health Service.

“I came to realize most of what I was seeing was preventable,” he says. “If I had to name one root cause of adverse health consequences on the reservation, it would be alcohol.”

Although the reservation is dry, for years residents crossed the border to purchase alcohol in Whiteclay, NE, where more than 4 million cans of beer were sold annually.

The town’s four beer-only liquor stores closed in 2017 after losing their licenses, but local residents say it lit a fire in the bootlegging market. It has also pushed people to harder alcohol like vodka and mixtures of gasoline and cleaning solutions, says Oglala Sioux Tribe Police Chief Robert Ecoffey.

According to the IHME, 27% of men and 9% of women were heavy drinkers in the county in 2012, and 34% of men and 12% of women were binge drinkers.

Ecoffey, who grew up on the reservation, came out of retirement in June to take the job. Combating drugs and alcohol with more manpower has been a priority, he says. He’s more than doubled the number of officers, providing police in each of the tribe’s nine districts to investigate more crimes and make more arrests.

Joseph Whiting’s daughter, Roberta Whiting, says although there is a greater police presence, she is still scared of the crime caused by illegal drugs. She worries about her father and checks on him constantly.

“I want to stay home,” she said. “It instills fear in me. Something terrible is going to happen. Young boys are dying because of crystal meth — they are hustling it and moving it. And girls, you see them drunk.”

Ecoffey also says he wants a treatment center to address the root causes of the tribe’s drinking problems.

“We can’t jail ourselves out of this. We have to break the cycle. It’s more than a law enforcement issue,” he says. “It’s a social issue for our tribe.”

Hope

June Two Bulls, 56, watches one of her grandsons play at the edge of the reservation at a popular outlook near Badlands National Park. She comes to sell hand-beaded jewelry to onlookers.

She spends time outside whenever she can, walking and hiking. She raised her grown sons to do the same. They work in construction, but cold weather has slowed the work. They do odd jobs and hunt deer, which they butcher and process by hand.

Both men are clean and steer clear of alcohol, and they’re raising their children to do the same.

“The drinking here is kind of scary,” said Eric Kills Enemy at Night, 23, one of Two Bulls’ sons. “Our people, it never was a part of who we were.”

The family grows gardens and picks berries, and Eric owns a small herd of cattle. But winter is hard with little work. There are more jobs off the reservation, but it is costly to commute. They will make it work, they say. They always do.

These are families, Ecoffey says, who will help transform the county.

“We have a lot of good, productive families on the reservation who work hard and raise families and try to make a difference,” he says.

Waiting, Hoping

June Two Bulls, 56, seen here and above, holds beaded jewelry she made.

Roberta Whiting understands the challenges of raising healthy, safe children on the reservation. She encouraged her daughter, now grown, to leave after she graduated from high school.

“Most people try to make a positive impact, but a lot of people are just stuck,” she says. “They need to get an education so they can help themselves and become productive members of society.”

Her daughter did leave, attended college, and now works as a teacher assistant in Rapid City, SD. And Roberta and Joseph, despite their concerns about safety and health, would like her to return to the reservation.

“Family is very, very important,” Roberta said. “This is what I have.”

Delores Pourier, health administrator for the Oglala Sioux Tribe, says the tribe has used grant-funded programs to address suicide, mental health, diet, and exercise. Many of them include cultural activities to draw youths back into tradition and give them a sense of identity.

“What are some things you can do when you’re depressed?” she says, and they teach them to bead, cook, and drum.

Beth Perkins, director of public health for the Indian Health Service, also believes that many of the addictions can be traced to generational trauma.

The focus now has to be prevention.

“They’re smoking, and it’s an addiction,” she says. “They’re doing it because of something in their life; what is the root cause?”

Both women see a gap in workforce development, vocational schools, and small businesses. Practicing Lakota traditions helps with identity, but it won’t solve everything, Perkins says.

“We’ll never get back to that because of technology,” she said. “Tradition can be a part of the solution. We can reintroduce sweat lodges and beading, but everything is moving, and we have to move with it.”

There is a lot to celebrate, they say, including education and economic and social efforts they hope will help transform the county. Those efforts include:

Red Cloud Indian School: The private Catholic K-12 school near Pine Ridge has invested heavily in the revitalization of the Lakota language and culture, and more than 90% of its high school graduates go on to college.

Lakota Funds: The Native Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI) has been providing loans and technical assistance to residents on Pine Ridge for 30 years. The fund also helps residents open bank accounts, start small businesses, and buy affordable homes.

Thunder Valley Development Corporation: It works to build community health through development of new social enterprises owned and run by local people.

Henderson, the Black Hills Center for American Indian Health founder, is working with tribal leaders to make Pine Ridge a smoke-free reservation. Tribal members of the nearby Cheyenne River Indian Reservation passed a clean air ordinance 3 years ago, Henderson says, the fifth tribe in the country to ban smoking in all outdoor public spaces, including powwow grounds, parks, and rodeo fairgrounds.

“The wheels are in motion on Pine Ridge,” he says.

This month, tribal law enforcement arrested two people on bootlegging charges in Kyle. The people were charged with distribution of alcohol, and officers believe the home, where three children lived, was a regular distribution center.

“I have interviewed so many people on the reservation, and they all know who the bootleggers are, but no one is ever arrested,” Henderson says. “This is the first time I can remember there being an arrest.”

Henderson says it’s a reminder that while there is much to overcome, hope is a never-ending virtue.

“My perspective of hope is that every child and every young adult has absolutely the best opportunity to become whatever he or she wishes to be,” he says. Warne agrees. “There’s a sense of hope because of the strength in our culture,” he says. “That’s the way out of our dire circumstances. We’ve been immersed in a racist society, and yet we’re still here.”

Hidden America; Children of the Mountains

Sawyer left a lot of key issues hidden in, “A Hidden America: Children of the Mountains.” Start with the theme song of her program, “You’ll Never Leave Harlan Alive,” which is a brilliant look at the unfair role of coal companies in exploiting land and mineral rights laws, dispossessing backwoods farmers from their land, and trapping them into the singular coal mining economy. The song ends: “And you spend your life digging coal from the bottom of your grave.

”Darrel Scot’s version is here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Su06XlGI-w8&feature=related

Patty Loveless’ version is here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e3IrnNAweM0&feature=related

As the Kentuckians for the Commonwealth have shown, mountaintop removal and strip mining, in general, have led to massive unemployment in the coal mining region, depopulated many of the rural communities, and polluted the watersheds. Here is a chart outlining the quality of life indicators vs. coal production statistics in the last 20 years in these coal counties: https://kftc.org/campaigns/mountaintop-removal-and-strip-mining

Instead of wringing their hands in sadness and powerlessness, the Kentuckians for the Commonwealth are some of the real heroes in region, working to bring economic and social justice to the coalfields. Sawyer should have taken the time to check out their work:

MTR-generalinfoIn fact, eastern Kentuckians and citizens from around the region will be converging on Frankfort today, as part of “I Love Mountains Day in Kentucky,” calling for an end to mountaintop removal and a shift toward a sustainable future for Appalachia.

Perhaps Sawyer can do another program on the need for green jobs in Appalachia. While poverty certainly exists in a scandalous way in Appalachia, it’s too bad Sawyer didn’t talk to some of the writers and artists and activists who have shattered the hillbilly stereotype, fought against the injustices of the coal companies, and shaped the way the America lives today. Some of these great heroes include author Silas House, whose novels and plays are some of the most compelling and fearless literary work today. Silas House should be a household name in America.

Diane Sawyer wants to understand the children of the mountains, she needs to interview Silas House. And finally, any discussion about drug addiction in Appalachia must examine the role of the OxyContin makers and their admitted deception in marketing the highly addictive painkiller.

I’ve read a number of comments on Facebook, ABC and various message boards. I am appalled at the lack of sensitivity and humanity from some people within our own region. Some have taken personal shots at Diane Sawyer. I’ve never been a big fan of Bruce Springsteen, but one of my friends shared this quote, “Dude, stop! You’re justifying the stereotype.” This time, the Boss may be right.

Many want to blame the impoverished for their plight. The common theme is, “we all have the same opportunities”, “they choose to live like this”, “it’s their own stupidity,” “they don’t have any pride”, “they should pull themselves up by their bootstraps and make something of themselves”, and I could go on and on. Yes, in some instances, it is a choice and some people know how to milk the system. But no caring person can blame an innocent child. And for those trying to “break the cycle”, it is a battle many of us can not begin to comprehend.

Whether you agree with Diane Sawyer’s approach or not, she is making us take a long hard look in the mirror.

One of my favorite songs is Brandon Heath’s, “Give Me Your Eyes”.

All those people going somewhere,

Why have I never cared?

Give me your eyes for just one second

Give me your eyes so I can see

Everything that I keep missing

Give me your love for humanity

Give me your arms for the broken hearted

Ones that are far beyond my reach.

Give me your heart for the ones forgotten

Give me your eyes so I can see

Maybe that’s where we should start, maybe we should ask ourselves,“What have I done to help correct this problem?” “Have I volunteered at a drug rehabilitation center, homeless shelter or literacy center?” “Have I provided a child with food or clothes?” “Have I invited someone to church?” I guess I’m realizing it is easy to complain and difficult to act. But, what have I done lately? I’ll ask you the same question. What have you done lately? And why do we always get so excited about foreign missions when we can find the same needs, many times even greater needs, less than five miles from our own doorstep.

I’m reminded of the verse, Matthew 25:44-45, “then they themselves will answer, ‘Lord, when did we see You hungry, or thirsty, or a stranger, or naked, or sick, or in prison, and did not take care of You?’ “Then He will answer them, ‘Truly I say to you, to the extent that you did not do it to one of the least of these, you did not do it to Me.’

That is where the answer lies, not in more government programs and handouts, but with you and me. Diane Sawyer described the people of our region as “brave and tough, filled with courage and hope.” Those are words of truth. The question now is, “What are we going to do?” Will I be the next mentor? Will you? Together we CAN change things, one life at a time. We appreciate your trust and God Bless America!

The most terrible poverty is loneliness and the feeling of being unloved.

-Mother Teresa

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZiE-b7kTXBM