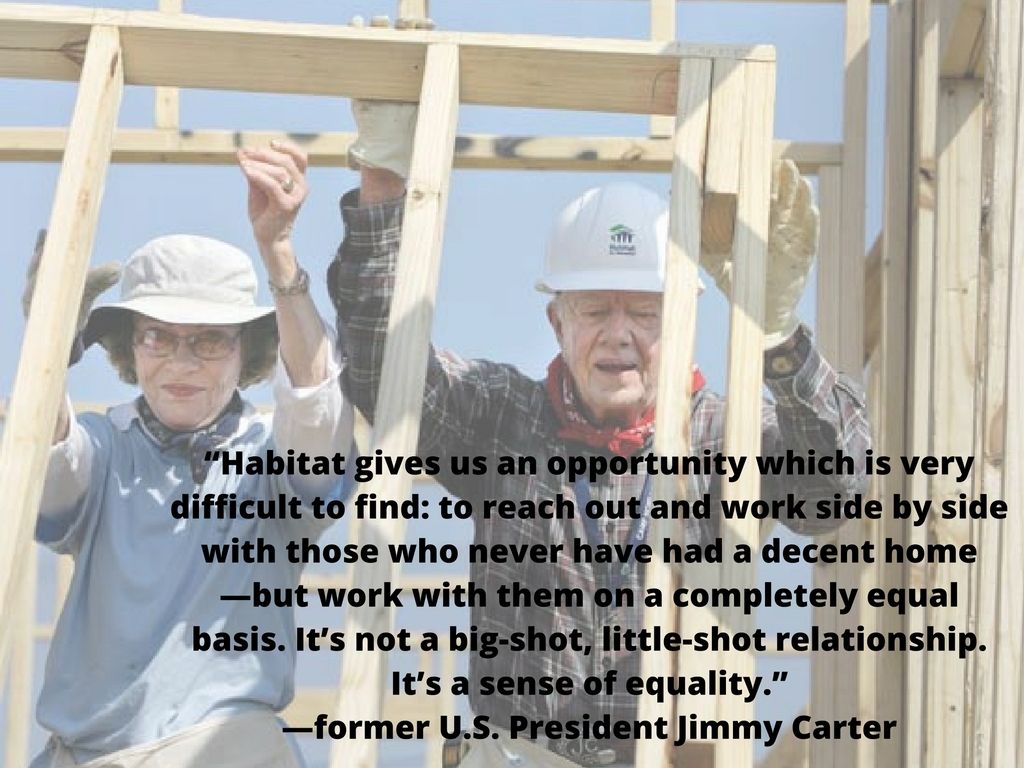

Jimmy & Rosalynn Carters Work Project

Jimmy Carter, (October 1, 1924 – December 29, 2024) in Plains, Georgia, at the Wise Sanitarium, where his mother worked as a registered nurse.[2] Carter thus became the first American president born in a hospital.[3] He was the eldest child of Bessie Lillian Gordy and James Earl Carter Sr., and a descendant of English immigrant Thomas Carter, who settled in the Colony of Virginia in 1635.[4][5]

In Georgia, numerous generations of Carters worked as cotton farmers.[6] Plains was a boomtown of 600 people at the time of Carter’s birth. His father was a successful local businessman who ran a general store and was an investor in farmland.[7] Carter’s father had previously served as a reserve second lieutenant in the U.S. Army Quartermaster Corps during World War I.[7]

How Jimmy Carter built houses for the poor until his final years | The Independent

He was the oldest living president and had been out of the White House for more than 35 years, but Jimmy Carter never stopped working to improve the lives of others — much of which included building homes for the needy. Even well into his 90s, Carter put on a hard hat and volunteered with Habitat for Humanity, the nonprofit organization he often partnered with through The Carter Center.

The one-term president — who died Sunday at his home in Plains, Georgia — worked alongside 103,000 volunteers in 14 countries to build, renovate and repair 4,331 homes with Habitat for Humanity for more than 35 years. Often, Carter and his late wife, former first lady Rosalynn Carter, volunteered together.

The couple first participated in a Habitat for Humanity project in 1984 in New York City. Carter discovered the organization while on a run. He recalled that he passed by a building and thought, “Rosalynn and I should come up and give them a hand.”

“When we left the White House, we could have done anything,” Carter once said. “But our choice was to volunteer as Habitat workers, and that’s been a life-changing experience for us.” In September 1984, the Carters and a dozen other volunteers made their way to New York, where they worked on a six-story apartment building that gave safe and affordable housing to families.

For one week, the Carters helped build 19 units and returned the following year to finish the building. The work unknowingly sparked an annual tradition for the Carters to spend one week volunteering with Habitat for Humanity in a different location around the world in what became known as the Carter Work Projects.

Habitat for Humanity was founded in Americus, Georgia — near Carter’s hometown of Plains — in 1976 by Millard and Linda Fuller. The organization aims to help build or improve homes for families in low-income or communities in need. It relies on volunteers and other Habitat for Humanity homeowners for manual labor, which is called sweat equity.

In recent years, Carter had experienced several health issues including melanoma that spread to his liver and brain. Carter decided to receive hospice care in February 2023 instead of undergoing additional medical intervention. His wife, Rosalynn Carter, died on Nov. 19, 2023, at age 96. He looked frail when he attended her memorial service and funeral in a wheelchair.

Carter left office profoundly unpopular but worked energetically for decades on humanitarian causes. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2002 in recognition of his “untiring effort to find peaceful solutions to international conflicts, to advance democracy and human rights, and to promote economic and social development.”

Carter had been a centrist as governor of Georgia with populist tendencies when he moved into the White House as the 39th U.S. president. He was a Washington outsider at a time when America was still reeling from the Watergate scandal that led Republican Richard Nixon to resign as president in 1974 and elevated Ford from vice president.

“I’m Jimmy Carter and I’m running for president. I will never lie to you,” Carter promised with an ear-to-ear smile. Also asked to assess his presidency, In Citizen Carter a 1991 documentary: Carter said, “The biggest failure we had was a political failure. I never was able to convince the American people that I was a forceful and strong leader.”

Despite his difficulties in office, Carter had few rivals for accomplishments as a former president. He gained global acclaim as a tireless human rights advocate, a voice for the disenfranchised and a leader in the fight against hunger and poverty, winning the respect that eluded him in the White House.

Carter won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2002 for his efforts to promote human rights and resolve conflicts around the world, from Ethiopia and Eritrea to Bosnia and Haiti. His Carter Center in Atlanta sent international election-monitoring delegations to polls around the world.

A Southern Baptist Sunday school teacher since his teens, Carter brought a strong sense of morality to the presidency, speaking openly about his religious faith. He also sought to take some pomp out of an increasingly imperial presidency – walking, rather than riding in a limousine, in his 1977 inauguration parade.

The Middle East was the focus of Carter’s foreign policy. The 1979 Egypt-Israel peace treaty, based on the 1978 Camp David accords, ended a state of war between the two neighbors. Carter brought Egyptian President Anwar Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin to the Camp David presidential retreat in Maryland for talks.

Later, as the accords seemed to be unraveling, Carter saved the day by flying to Cairo and Jerusalem for personal shuttle diplomacy. The treaty provided for Israeli withdrawal from Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula and establishment of diplomatic relations. Begin and Sadat each won a Nobel Peace Prize in 1978.

By the 1980 election, the overriding issues were double-digit inflation, interest rates that exceeded 20% and soaring gas prices, as well as the Iran hostage crisis that brought humiliation to America.

These issues marred Carter’s presidency and undermined his chances of winning a second term. Former President Jimmy Carter was known globally for his diplomacy and humanitarian work.

The ‘Carter effect’: How the former president gave cancer patients hope.

The world of medicine will remember him not only as a person who beat the cancer that spread in his body, but also as arguably the most influential voice to raise awareness of a cutting-edge cancer treatment: immunotherapy.

Even people who have never heard that term usually know it was “the Jimmy Carter drug” that helped save his life. Carter’s successful cancer treatment “would have been considered a miracle just 15 to 20 years ago,” said Dr. Adam Friedman, chair of dermatology at George Washington University. “The ‘Carter effect’ spawned a new era of hope for patients who would ordinarily be hopeless.”

Advances in melanoma

In 2015, a person with metastatic melanoma — a form of skin cancer that has spread throughout the body — was unlikely to survive more than six months, and possibly not even six weeks if he or she happened to be 90 years old. Carter believed that was his fate when he announced in August of that year that melanoma has spread to his liver and his brain.

“I’ve had a wonderful life,” Carter said at a media briefing at the time. “I feel that it’s in the hands of God and my doctors, and I’ll be prepared for anything that comes.” There are many possible reasons Carter, who died Sunday at age 100, survived as long as he did. He had access to some of the best cancer doctors in the world as he underwent surgery and radiation.

He was a man of strong faith and lived with purpose, which he spoke about at the 2015 briefing.

He also revealed that he would be treated with a relatively new immunotherapy called pembrolizumab, sold as Keytruda. Keytruda works by harnessing the power of the body’s immune system to attack cancer cells. “This is a medicine that they use for melanoma that enhances the activity of the immune system,” he said at the time.

The Food and Drug Administration approved the first immunotherapy drug, called Yervoy, just four years earlier, in 2011. Keytruda wasn’t greenlighted until 2014. Both were originally intended for the notoriously hard-to-treat melanoma.

Before that, there hadn’t been any new approaches for melanoma in decades, said Dr. Amod Sarnaik, a professor of cutaneous oncology and immunology at Moffitt Cancer Center’s Cutaneous Oncology Program in Tampa, Florida.

“It was a rather depressing time,” he said.

Carter’s willingness to speak openly about the new approach, Sarnaik said, prompted excitement and investment in the field.

“In the absence of this unfortunate thing happening to President Carter, I don’t think that we would be talking about immunotherapy in the national domain,” he said.

Since Carter’s diagnosis, at least 15 new treatments for stage 4 melanoma have been approved, said Dr. Michael Davies, chair of the department of melanoma and medical oncology at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. Some immune therapies are used in combination with other cancer drugs or even surgery at earlier stages of disease.

And its use has expanded greatly. Varying forms of immunotherapy are used to treat a wide variety of cancers, including lung cancer, breast cancer, endometrial cancer, head and neck cancer and some rare forms of colon cancer.

Studies of its possible use in treating pancreatic cancer are also underway, said Dr. Suresh Ramalingam, executive director of the Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University, where Carter was treated. Ramalingam wasn’t directly involved in Carter’s care.

“Immunotherapy has been a game changer,” Ramalingam said. “We are seeing patients live longer and live better because of what immunotherapy has meant to the field of cancer.”

In early June, researchers at NYU Langone Health reported that patients with metastatic melanoma given a combination of pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and an experimental mRNA vaccine targeting their cancer cells were living longer without additional spread of their disease compared to people who got Keytruda alone.

Three-quarters of patients who got both therapies had no recurrence three years later, compared to 56% in the Keytruda-only group. The combination group had an edge in survival, too: 96% versus 90%. Immunotherapy doesn’t work for everyone, offering only about a 30% to 60% success rate, depending on the cancer and the course of treatment. “We’re not satisfied with that,” Sarnaik said. “We want a 90% to 100% response rate, and we’re nowhere near those numbers.”

There can be side effects. Immunotherapy can kick the immune system into overdrive, causing a variety of inflammatory responses. People who develop lung inflammation may need supplemental oxygen. Such a complication in the colon, called colitis, can be life-threatening, Davies said.Still, it doesn’t usually come with hair loss, nausea, extreme fatigue and other side effects historically associated with chemotherapy.

“Many of my patients on immunotherapy continue in their jobs.

“They get the treatment in the morning and go to work in the afternoon,” Colleagues who treated Carter were “immensely grateful” for his contribution in raising awareness of immunotherapy, “When we see patients like President Carter beat their cancer, that is the positive reinforcement that drives us to do even better,” Ramalingam said.

…