THIS IS WHY THEY STILL CALL IT CAPE FEAR . . .JULY 12, 2022, CHUCK FAGER

I have friends who are shocked that I drink bottled water and have for years. This article explains why. I have lived in this “forever chemical-soaked” region for 20 years. Someday (maybe; not very likely) this toxic horror show will get fixed. In the meantime, I have to drink water every day. I choose stuff that’s been filtered a few times more than what

comes from the top; so, sue me.

The cast of villains here includes everybody’s favorites: for lefties, big corporations spew the poisons nonstop & laugh at regulations. For righties, “big government” has spent lots and failed miserably; so too have the “small” & supposedly “closer-to-the-people” units: cities, counties, the state. For nativists, foreigners (esp. China) are in on it too, owning

the world’s biggest hog slaughterhouse nearby. Etc.

Maybe we should try that old standby, Thoughts and prayers.

I welcome the exposure this article delivers. But I’m more than a little jaded: in these twenty years, big journalistic exposés have floated by every few years. Usually they’re pretty good, now and then a reporter gets a prize. And nothing seems to change.

So, take a look, while I go refill some plastic jugs at our community co-op super filter

water machine.

Cancer fears plague residents of US region polluted by ‘forever chemicals’ | The Guardian

In Wilmington, North Carolina, 50-year-old Tom Kennedy thinks it might be time to stop fighting the cancer that started in his breast and now grips his spine. He’s endured 85 chemotherapy treatments since an inverted nipple sent him to the doctor five years ago, and he fears the endless struggle to keep him alive is more than his daughters can bear.

He wonders if it’s time to let death take him so his family can move on.

Cancer and questions plague North Carolina residents of PFAS-polluted region

Exposure to harmful PFAS remains almost impossible to escape – particularly for the people of the Cape Fear River basin. Cancer fears plague residents of US region polluted

by ‘forever chemicals.’ Exposure to harmful PFAS remains almost impossible to escape – particularly for the people of the Cape Fear River basin.

A deadly cancer has already taken 43-year-old Amy Nordberg Shands away from her family, of Winnabow N.C. Nordberg died in January after a three-year battle with a vicious cancer that followed the development of multiple sclerosis. The cancer moved through her body faster than doctors expected, enveloping her colon and invading her bone marrow.

Kennedy and Nordberg are only two among many sick and dying people who live

in the Cape Fear River basin of North Carolina, where environmental testing has found persistently high levels of different types of toxic compounds known collectively as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS.

Several industries operating in the area have been using PFAS for years, while DuPont

and successor Chemours have been producing the chemicals at a plant in Fayetteville

situated along the river. PFAS are typically part of the manufacturing of thousands of

products resistant to water, heat and stains.

Some of the most widely studied types of PFAS have been linked to a range of human health problems, including cancers. They’re called “forever chemicals” because they

don’t degrade and accumulate in the environment and human bodies.

But despite more than 20 years of warnings from public health advocates, exposure

to the chemicals remain almost impossible to escape – particularly for the people of

the Cape Fear River basin.

The physical and emotional suffering that comes with living in an area polluted by toxins is ripping through families, scarring lives and short-circuiting dreams for the future.

Making it all worse is the fact that while many people feel certain the health problems,

they or their friends and loved ones are experiencing are connected to the PFAS pollution, confirming those suspicions has been almost impossible. State and federal regulators have pushed back against requests for in-depth studies.

“The response is not proportional to the harm that’s been committed here,”

said Emily Donovan, executive director of the Clean Cape Fear advocacy group,

created in 2016 in response to the crisis.

A woman with her children on the Cape Fear River.

Photograph: Allison Joyce/The Guardian

SPLASHING in PFAS Foams

Chemours has acknowledged the concerns about PFAS contamination and says it has been working for several years to address them with residents and regulators. Still, the signs of contamination are all around. On beaches in Oak Island, near where the Cape Fear spills into the Atlantic Ocean, children build sandcastles and splash in PFAS foam, a form of toxic waste. When it rains, PFAS-laced foamy water bubbles in gutters in the town of Leland.

PFAS contamination has been documented throughout the region – in drinking water;

in air and soil samples, in crops, in livestock and fish; and, notably, in blood samples taken from people who live and work in the region. The basin is considered an important natural resource for drinking water, agriculture, and recreation. But the 450,000 residents and another 200,000 tourists who visit the area annually risk exposure to PFAS contaminants, experts say.

The PPA facility in Fayetteville.

Photograph: Gerry Broome/AP

It all makes the region a perfect “petri dish” for PFAS research – a chance to study how

40 years of exposure to a broad cross-section of PFAS affects a large population’s health,

according to a coalition of community and the environmental justice groups that have demanded comprehensive research program on 54 PFAS emitted by the Chemours plant.

The EPA has rejected the requests and has said it will analyze only seven PFAS and attempt to extrapolate their health impacts and toxicity data across the entire class of

over 9,000 PFAS compounds. Last month, the coalition sued the EPA over the issue.

“We’re outraged – they basically gave us nothing,” said coalition attorney Bob Sussman.

The problems in Cape Fear persist even after the Biden administration last year launched a sweeping multibillion-dollar project aimed at reducing PFAS use and public exposure to the chemicals. Because the chemicals don’t naturally break down, meaningfully reducing levels in drinking water near the plant and remediating the land will likely take decades, said Detlef Knappe, a PFAS researcher with North Carolina State University.

“Peoples’ lives really got turned upside down because it’s not just drinking water, it’s likely food, fishing, swimming in the lakes, property values: all of these things won’t change for the foreseeable future,” Knappe said. “It’s a tragedy, a travesty, and, yes, it’s a result of four decades of Chemours basically operating without oversight in terms of those compounds.”

DuPont owned Fayetteville Works until it spun off Chemours in 2015 to protect itself from PFAS-related legal liabilities. Researchers estimate Cape Fear residents spent decades drinking water with staggering PFAS levels exceeding 100,000 parts per trillion (ppt) –

far above the federal advisory level of 70 ppt for two kinds of PFAS. Some public health groups say no amount above 1 ppt is safe.

Low-income residents who can’t afford costly filtration systems, who subsist on

fish in the river and who have less access to information are more vulnerable.

Though Chemours is not the only PFAS source in the watershed, a study Knappe co-authored linked a significant portion to Fayetteville Works. Chemours states on its website that over the last five years it has “taken numerous steps to dramatically reduce water discharges and air emissions” of PFAS and other compounds from the Fayetteville Works plant.

In a statement to the Guardian, Chemours said it was fulfilling its pledge to sharply

reduce PFAS contamination and noted it has spent $400 million on pollution controls. The company said it operates with transparency and claimed, “no other company in North Carolina … has made a similar commitment.”

Though Chemours stopped discharging PFAS directly into the Cape Fear River in 2017,

the aquifers around Fayetteville still teem with decades worth of contamination.

The chemicals move into the river and wildlife and that helped push drinking water levels around Wilmington to 380 ppt in January – well above what’s considered safe. Almost all of the 10,000 wells tested in the region show some level of PFAS contamination and over two-thirds are above the threshold that requires Chemours to provide filtration.

Fayetteville Works installed air pollution controls in 2020 that partially reduced emissions, but state records show some continues. The chemicals are volatile, also meaning they can move from the ground into the air.

Then, as PFAS drop or rain down on the region’s sandy, red soil, they can move back into the aquifers and re-contaminate drinking water. The toxins have even been found at high levels in kale, lettuce, tomatoes, blueberries and blackberries.

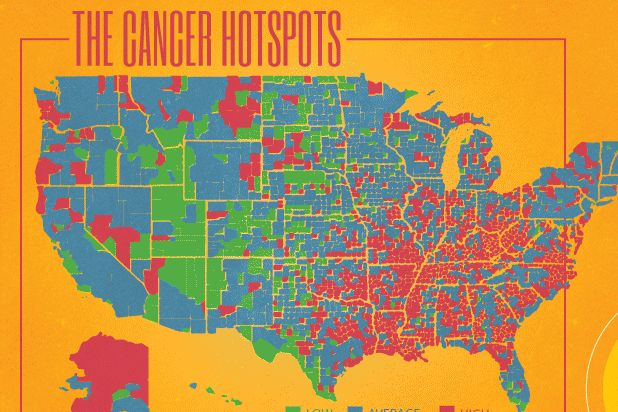

This Red Area Showcasing the Poorest Area Quality in the United States.

‘I have to do what’s right for them’

Though regulators have refused to conduct blood studies, an ongoing North Carolina State analysis of blood samples from more than 500 residents has confirmed the presence of some Chemours-produced PFAS compounds in the blood samples.

About a week after an early May spine surgery, Kennedy lay weakened in a rehabilitation center bed, his contorted, frail body covered in bruises and sores. His wife, Christine, helped him change positions and sip juice from a straw. Though doctors say he could live several more years if he continues treatments, Kennedy said his constant sickness is ruining the lives of his children, trapping them in a steady state of grief.

“How many times can they see me get put into an ambulance?” he asked from

the hospital beds. “Who wants to die? I don’t, but I have to do what’s right for them.

BETH MARKESINO, 2021 (INTERVIEW VIDEO AND TRANSCRIPT)

Beth Markesino, 38, who lives roughly 11 miles away from Kennedy, still mourns the loss of a 2016 pregnancy she believes is connected to the fact that she drank water potentially laced with PFAS. About 23 weeks into her pregnancy, sharp stomach pain sent Markesino to doctors who found her unborn child had not developed kidneys, a bladder, or bowels, and wasn’t producing amniotic fluid.

Six months after burying the boy she named Samuel at a family plot in Detroit,

Markesino saw a local news story reporting PFAS linked to pregnancy complications

had contaminated her drinking water.

“I’ll never know 100% if that’s what happened with my son, but I drank the water,

and I drank tons of it,” Markesino said. She has since suffered from PFAS-linked health problems that include ovarian cysts, thyroid cysts and tumors.

Over 70 miles west, near Fayetteville, 38-year-old Adrian Stokes suffers from

health problems that include thyroid disease, kidney cysts, pulmonary embolisms,

an autoimmune disorder, an enlarged liver, and debilitating exhaustion.

“I feel like I could probably kill myself because of how bad I hurt,” he said.

Pets he once had also suffered a range of health problems.

A few miles away, US army veteran Mike Watters founded a citizens’ group to seek answers on PFAS contamination concerns after his three dogs died of pancreatic cancers. He helped connect 30 local owners of sick dogs and horses with university researchers who drew blood from the animals, tests that confirmed the animals were contaminated with PFAS too.

The blood test results, and other data has been shared with state officials, and the legislature did create a “PFAS Collaboratory” made up of university researchers to

study contamination. But the Collaboratory can’t enforce laws, fine companies or

order cleanups.

And even though Chemours is operating under a 2019 consent order issued by regulators, the company has regularly violated that order.

‘We thought we had time’

For Amy Nordberg’s husband Jonathan Shands, the push for research comes too late.

He has little doubt about who and what to blame for her January death. Tests showed Chemours’ PFAS not only in the family’s drinking water, but also in his wife’s blood.

Before she developed cancer, Nordberg was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, which new science links to PFAS exposure. Then, over the course of three agonizing years, a cancer that first attacked her sinuses and face spread rapidly.

Nordberg had been determined to live long enough to see the couple’s daughter Izzy, 15, graduate from high school. But the cancer moved too fast, attacking her colon and bone marrow late last year. “We thought we had time,” Shands said.

“But none of that happened. Chemours can hide behind lawyers, and they can do whatever they want to do.

The fact is, she is no longer here. And that’s not going to bring her back.”

More than 8 million Illinoisans get drinking water from a utility were

forever chemicals have been detected, Tribune investigation finds.

CANCER ALLEY LOUISIANA (1987- )

CONTRIBUTED BY: SUMAYA ADDISH

Cancer Alley Louisiana, known in the ’80s as “Chemical Corridor.”

– “Cancer Alley” is an 85-mile-long stretch of the Mississippi river lined with

oil refineries and petrochemical plants, between New Orleans and Baton Rouge.

– People living in the area are more than 50 times as likely to get cancer than

the average American.

– For years, residents have suffered from illnesses, but they’ve been unable

to prove a causal connection between industry and the health effects.

Related: United Nations experts condemn pollution of Cancer Alley

as environmental racism (lailluminator.com)

When residents of St. Gabriel, Louisiana took note of the large number of fellow community members being diagnosed with cancer along Jacobs Drive, the community nicknamed the street “Cancer Alley.” As the number of cancer cases steadily grew within their community and across the state, Cancer Alley’s reach extended 85 miles along the banks of the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans.

The alley had a concentration of plastic plants, oil refineries, and petrochemical facilities that make it one of the most toxic areas in the nation. Before being named “Cancer Alley” however, the region was originally labeled “Plantation Country,” describing the grim past in which enslaved Africans underwent forced labor.

The lack of environmental regulation in St. Gabriel and other neighboring cities has led to a plethora of ailments plaguing the residents, ranging from cancer to mental and physical developmental disorders. In 2002, Louisiana had the highest death rate due to cancer in the nation, and the annual carbon dioxide emission rate in the St. James parish, where St. Gabriel is located, equaled that produced by approximately 113 countries, according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Despite the grim statistics of the threats posed by these facilities, industrial expansion continues especially in areas with high percentages of poor and Black residents.

Cancer Alley, Louisiana, is one of many examples of environmental racism.

It is home to 45,000 citizens, the majority of whom are poor and Black and who continue to be poisoned with toxic waste which generate various life-threatening illnesses. While reality remains grim, many residents of Cancer Alley have organized themselves to protest the further destruction of their city. RISE St. James, a grassroots organization founded in 2018, organized its first protest in response to the St. James Parish (County) Council approving the “Sunshine Project,” which would build another large plastic plant in the area.

During the march, protesters held signs reading, “Green Jobs. Green Infrastructure” & “Clean Air. Clean Water. And Clean Soil”. In response the Louisiana state legislature in May of 2021, enacted a bill criminalizing protester activity with a three-year minimum prison sentence. The bill was vetoed by Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards. Despite suppressive actions taken by lawmakers, community members continue to advocate for their environmental and civil rights.

Between 2009 and 2016, air pollution in the U.S. decreased significantly.

Although Cancer Alley remains one of the most polluted areas in the nation, industry expansion in the area has slowed dramatically, providing some relief. In January of 2021, President Joe Biden signed Executive Order 13990, Protecting Public Health and also the Environment and Restoring Science to Tackle the Climate Crisis. This executive order pledges the federal government to intensify its enforcement of environmental regulations in areas like Cancer Alley that are economically and socially marginalized.

Subjects: African American History, Places Terms:

20th Century (1900-1999), United States – Louisiana

3,247 Elementary Schools are Exposed to Monsanto’s Toxic Weed Killer.