Autism’s Gut-Brain Connection Medical University of Vienna – Search (bing.com)

Can You Develop Autism Later In Life? (msn.com)

An international research team has found that in mice, there is a connection between exposure to intestinal flora during gestation and the development of the brain’s protective cells.

One of the researchers, Hans Herbert, a professor in biotechnology at Stockholm’s KTH Royal Institute of Technology, says that understanding the link between gut bacteria and the development of what is known as the blood-brain barrier could “have important significance for the prevention and treatment of neurological disorders such as autism in humans.”

The blood-brain barrier is a layer of cells that line the blood vessels throughout the brain. This layer is held together by tight junctions that prevent small molecules from diffusing through the gaps between the cells. The barrier serves as a filter to prevent harmful substances from passing into the brain tissue from the bloodstream.

Herbert and other researchers have shown that mice deprived of exposure to natural intestinal flora – or gut bacteria – during the fetal development period had higher permeability of the blood-brain barrier than mice exposed to maternal gut bacteria.

The “leakiness” of the blood-brain barrier continued even into adulthood for the bacteria-free mice. This permeability was associated with a lower incidence of the proteins that make up the blood-brain barrier.

But when these adult mice were exposed to gut bacteria, the permeability of the blood-brain barrier decreased and the presence of the proteins increased.

The researchers concluded that communication between flora in the intestine and the blood-brain barrier begins during gestation and that it then continues throughout life.

The results were published November 19, 2014 in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

Herbert says the findings may be significant for understanding how neurological disorders develop.

“There are hypotheses about how changes in the presence of gut microbiota can lead to problems in the function of the brain and nervous system. It also has been hypothesized that autism is related to the blood-brain barrier function.”

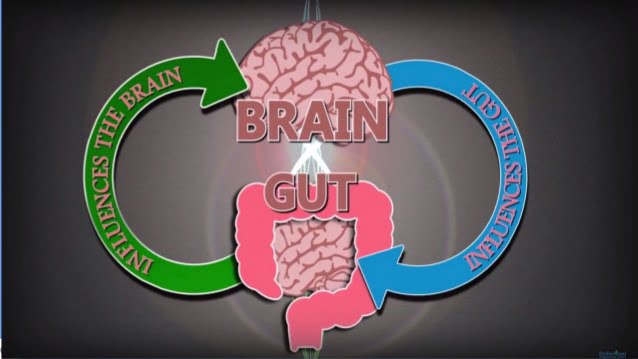

Stress can send your stomach into a painful tailspin, causing cramps, spasms and grumbling. But trouble in the gut can also affect the brain.

This two-way relationship may be an unlikely key to solving one of medicine’s most pressing—and perplexing—mysteries: autism. Nearly 60 years after the disorder was first identified, the number of cases has surged, and the United Nations estimates that up to 70 million people worldwide fall on the autism spectrum. Yet there is no known cause or cure.

But scientists have found promising clues in the gut. Research has also revealed striking differences …..in the trillions of bacteria — collectively known as the microbiome—in the intestines of autistic and healthy children. However the gut bacteria in autistic individuals aren’t just different. Researchers at the California Institute of Technology have shown for the first time that they may actually contribute to the disorder. Last month, they reported in the journal Cell that an experimental probiotic therapy alleviated autism-like behaviors in mice and are already planning a clinical trial.

Today autism is treated primarily through behavioral therapy. But the new study suggests that treatment may one day come in the form of a probiotic—live, “friendly” bacteria like those found in yogurt. “If you block the gastrointestinal problem, you can also treat the behavioral symptoms,” Paul Patterson, a professor of biology at Caltech who co-authored the study, told SFARI.org. University of Colorado Boulder professor Rob Knight hailed the finding as “groundbreaking” in a commentary in Cell.

Autism is a complex spectrum of disorders that share three classic features – impaired communication, poor social engagement and repetitive behaviors. On one end of the spectrum are people who are socially awkward but, in many cases, incredibly bright. At the other extreme are individuals with severe mental disabilities and behavioral problems.

Among autistic children’s most common health complaints? Gastrointestinal problems. Although estimates vary widely, some studies have concluded that up to 90 percent of autistic children suffer from tummy troubles. According to the CDC, they’re more than 3.5 times more likely to experience chronic diarrhea and constipation than their normally developing peers.

Following these hints, Arizona State University researchers analyzed the gut bacteria in fecal samples obtained from autistic and normally developing children. They found that autistic participants had many fewer types of bacteria, probably making the gut more susceptible to attack from disease–causing pathogens. Other studies have also found striking differences in the types and abundance of gut bacteria in autistic versus healthy patients.

But is the gut microbiome in autistic individuals responsible for the disorder? To find out, Caltech postdoctoral researcher Elaine Hsiao engineered mice based on earlier studies showing that women who get the flu during pregnancy double their risk of giving birth to an autistic child. In the mouse model, pregnant females injected with a mock virus gave birth to pups with autism-like symptoms, such as obsessive grooming, anxiety and aloofness.

The mouse pups went on to develop so-called “leaky gut,” in which molecules produced by the gut bacteria trickle into the bloodstream, possibly reaching the brain—a condition also seen in autistic children.

But how did these bacteria influence behavior? To find out, Hsiao analyzed the mice’s blood. The blood of “autistic” mice contained a whopping 46 times more 4EPS, a molecule produced by gut bacteria, thought to have seeped from their intestines. What’s more, injecting healthy mice with 4EPS made them more anxious. A similar molecule has been detected at elevated levels in autistic patients.

Hsiao then laced the animals’ food with B. fragilis, a priobiotic that’s been shown to treat GI problems in mice—and the results were jaw-dropping.

Five weeks later, the leaky gut in “autistic” mice had sealed up, and the levels of 4EPS in their blood had plummeted. Their gut microbiomes had come to more closely resemble those of healthy mice—and so did their behavior. They were less anxious and more vocal, and stopped obsessively burying marbles in their cages.

But the treated mice remained aloof when a new mouse was placed in their cage. “This is a real limitation in the conclusions from this study as, in many ways, social interaction deficits are at the core … of autism,” Ted Abel, a professor of biology at the University of Pennsylvania, told SFARI.org.

What’s more, a probiotic may only help the subset of autistic patients who experience GI problems, Hsiao said. And only a clinical trial will reveal whether the results also apply to humans.

Still, autism researchers shouldn’t underestimate the importance of gut bacteria, said John Cryan, a professor of anatomy and neuroscience at University Cork College. In 2011, his group reported in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that probiotic-fed mice were less anxious and produced fewer stress hormones. “You have this kilo of microbes in your gut that’s as important as the kilo of nerve cells in your brain,” he said. “We need to do much more studies on autistic biota.”

For autistic patients and their families, however, even a supplemental therapy for a subset of sufferers is a huge step forward. “It’s really impactful, this notion that by changing the bacteria, you could ameliorate what’s often considered an intractable disorder,” Hsiao said. “It’s a really crazy notion and a big advance.”

This piece comes from our partner OZY. Melissa Pandika is a lab rat-turned-journalist with eye to all things science, medicine and more.

*With some reporting from SFARI.org. Updated August 12, 2014.